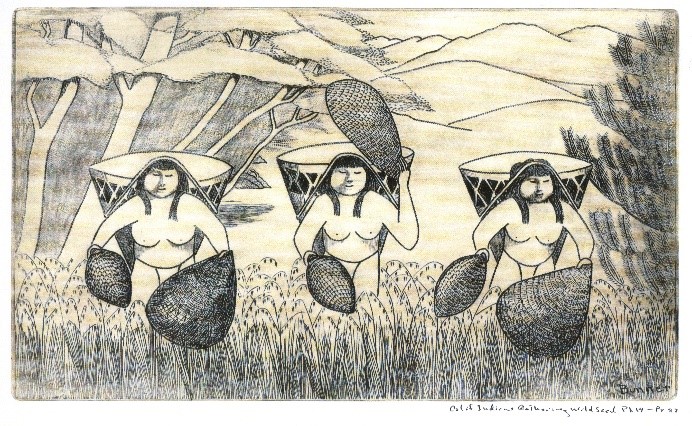

Contemporary California Indians

Beverly R. Ortiz, First People of the East Bay

The early 1870s were a watershed in the history of American attitudes toward the California Indian. After 1871 the Indians were no longer perceived by whites as serious threats to the prosperity and development of the state…During the later nineteenth century the majority of California Indians subsisted on the fringes of white settlements, where they continued to work as general farm, laborers, herdsmen, grain harvesters, fruit pickers, and domestic servants…Only a minority of the California natives (perhaps one-fourth) remained on the old federal reserves…

Whatever the prospects for the survival of the California Indians as an “independent genetic entity,” their cultural survival is ensured. In the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s Indian people throughout the state demonstrated a growing interest in the revival, preservation, and demonstration of their past native cultures. This resurgence has produced some remarkable results.

Generally the tribes that have been able to remain on at least a portion of their traditional lands, have been the most successful in retaining elements of their aboriginal wayh of life. (He gives as examples the Cahuillas and Hupas.)

From James J. Rawls, Indians of California, pp.205 ff.

In the 1980s this new interest in California Indian studies became apparent. A series of California Indian conferences began and a new generation of Indian scholars included Native Americans. Within the community there was a resurgence of interest in traditional religion, including dance and music, and in basketmaking and other crafts. The publication of Heyday Books’ quarterly News from Native California now provides articles on ethnography, ethnohistory and current developments on a board range of topics.

From Sylvia Brakke Vane, “California Indians, Historians, and Ethnographers,” pp. 339-340. (In Indians of California, 1992)

California Indian peoples have tended to be rural peoples residing mainly on reservations or rancherias or in the local communities near where they are members. Most still consider the traditional territories of their ancestors, as well as their reservation or rancherias, as “homeland,” a place to which they and their descendants will always return, as they have in recent years in greater and greater numbers. It is a sacred and historic space, a physical reminder of one’s philosophical and historic roots, a place where traditional ways are understood and welcome. It is preferred place to be, the place where kinfolks and old friends live, the place where one’s traditional religious ways are available….

Many native Californians may live away from their lands for the better part of a lifetime and yet come back frequently or finally to a way of life compatible with their cultural ideals and with close involvement with their family and friends. This pattern has contributed, in part, to cultural persistence, since those who return may return with expectations of what was remembered when they left…

The United States government withdrew most federal responsibility for native Californians in 1955 under Public Law 280/ Each reservation or rancheria now elects a body of officials, known variously as a business-committee or tribal council. These officials represent the group and act as a liaison between the group and outsiders such as the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs…

For the most part, California Indians have adopted many of the ways of the European world. …In many other ways, however, traditional native Californian culture, values, art, dance, music, psychology, and the attachment to traditional lands contribute to the rich cultural fabric of the state…

Indian languages, though spoken less and less as first languages, are being maintained and revived among many groups. Linguists have been working very actively with California Indians to this end….Several organizations, such as the California Indian Education Association, American Indian Historical Society, Hupa Cultural Center, and Malki Museum, have aggressively examined, criticized, and provided to teachers new teaching materials dealing with Indian culture and history.

In contrast to reservation-based groups, many California Indian groups never received federal acknowledgment. These groups, therefore, have no land-base or special relationship with the federal government. Now, over thirty previously-unrecognized groups, such as the Ohlone of the San Francisco Bay Area, are actively engaged in requesting such recognition. These groups have contributed a new dynamic thrust to the visibility of Indian cultures.

In the major population centers of California, from San Francisco and Oakland south to San Diego, different forms of Native American cultural development are under way as California Indians and others throughout the United States establish residence in major urban areas. Bringing with them diverse tribal and cultural backgrounds, they contribute to a new cultural diversity and to an emerging pan-Indian consciousness and institutional structure.

From Lowell J. Bean, Indians of California, pp. 321-323

East Bay Indians

New research has revealed information about the language and culture of many California tribes, including the East Bay’s Ohlone/Costanoan, Bay Miwok and Northern Valley Yokuts.

Ethnographers, linguists, archaeologist, anthropologists and demographers are studying mission records, analyzing work done by researchers such as J. P. Harrington, recording oral histories from native people and writing about California Indians (past and present) in books and magazines. Errors in Alfred L. Kroeber’s famous Handbook of California Indians (1925) have created a variety problems for East Bay Indians including misperceptions about their cultural history and problems with federal recognition.

Research on the Bay Miwok has appeared in academics journals, reports from the Los Vaqueros Project and other archaeological reports. Randy Milliken’s book, A Time of Little Choice, is one example of recent scholarship which has brought insights into the traditional lives of East Bay Native Americans. See the Selected Bibliography for other sources.

Laws have been passed since the 1960s to help protect Indian rights. Some of these include the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, the Antiquities Act (1906), the Archaeological Resources Protection Act, the National Historic Preservation Act, National Environmental Protection Act and the California Environmental Protection Act. Government regulations such as N.A.G.P.R.A. (Native Americans Grave Protections and Repatriation Act of 1990) have put some restrictions on the scientific recovery and invasive study of cultural material and, at the same time, have enabled Native Americans to take ownership of their cultural heritage.

California Indians today live throughout the state both in cities and in rural areas. Some live in one of over 100 traditional communities ranging in size from a single-family, single-acre rancheria to the 142 square mile Hoopa Valley Reservation in Humbolt County. The 2000 census listed 105 reservations or rancherias in the state.

Compiled by Beverly Lane, Sources at conclusion

Sources

Bean, Lowell J. ed. Indians of California (San Francisco: California Historical Society), Fall 1992.

——-, The Ohlone Past and Present Native Americans of the San Francisco Bay Region (Menlo Park: Ballena Press), 1994.

Rosenthal, Jeffrey S., Randall T. Milliken and Stephen Mikesell, Naval Weapons Station, Seal each, Detachment Concord, Integrated Cultural Resources Management Plan for the years 2000-2005 (Davis, CA: Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Inc., Box 413), 2000.

Rawls, James J., Indians of California A Changing Image (Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press), 1984

From Bay Miwok Readings, 2003.

After the first contact, there were years of respite in the Bay Miwok homeland, while the Spanish focused on the San Francisco peninsula.

Mol-le and her family, and the whole tribe of Chupcans, had other direct encounters with the Spanish in subsequent years, but it wasn’t until later in her life that the exploratory visits were transformed into invasion. By 1795 Franciscan missions and Spanish soldiers were having a devastating effect on the Indians of the Bay Area. That history is described in detail elsewhere.

The Spanish encroachment into the inner valleys of the East Bay (1795-1812) occurred during Mol-le’s old age. Since none of her immediate family came into the missions, it seems likely that they were among those who chose to avoid, evade, fight or die for their way of life. Nearly forty years passed from the first Spanish exploration until Mol-le and her family were taken into the mission. The events leading to that are dramatic.

The construction of Mission San Jose in 1797 marked the beginning of the end for the Chupcans as a tribe. There was immediate resistance all over the inland East Bay. Plans were made for attacks and there were warnings from the Saclan and Volvon to others not to cooperate. At same time that the Padres carried the carrot of promised material and spiritual power to the Bay Miwok, the soldiers brought the sticks of fire and horses to encourage and chastise those slow to submit to Christian/European civilization.

The Saclans of the Lafayette area attempted to defend their villages by digging trenches around them to stop the horsemen. But like all out-gunned defenders, they were reduced to hit and run battles and escape and evasion. Some sought refuge with their neighbors, the Chupcans.

The records suggest that nearly every year from 1800 to 1805 the soldiers came north from San Jose to recover mission runaways who had sought refuge in Diablo Valley and the Contra Costa environs. It was in one of these excursions into the swampy wilderness of the Chupcans that one of the soldiers named the place Monte del Diablo (Wilderness or Thicket of the Devil), after which Salvio Pacheco named his rancho in Diablo Valley. Later the name was transferred to present-day Mount Diablo.

About this time, the Chupcans decided to completely abandon their villages in Diablo Valley. A few had gone into the missions, but most left to settle near many of their relatives by marriage in Solano County. Some were married to the Carquines of Benicia, but many were married with the Suisuns further up the north side of Suisun Bay.

By the first decade of the nineteenth century the padres in San Francisco and San Jose were greatly distressed by the resistance of the East Bay inland natives. On February 28, 1807, Padre Abella of Mission San Francisco wrote to the governor: “I give you the cursed news that the pagan natives and runaway Christians have killed between eleven and thirteen neophytes of this mission.” He then describes a series of events that begin when a Tatcan child of the San Ramon Valley area died and his parents and others escaped back to Contra Costa. Battles ensue between various Indian tribes. The padre said, “You can imagine the confusion here. I myself thought about running away so that I would not have to face it.” He called on the Governor to authorize a punishing expedition.

In 1810, the third incident in six years of mission Indian killings occurred on the northern shore of Suisun Bay. Seven neophytes had obtained passes, perhaps to try to persuade their pagan relatives to join the mission. Those who visited the Carquins at Benecia got back alive. The three who had continued on to Suisun were killed by their relatives, according to pagan Chupcan witnesses. These reported deaths brought on a large Spanish expedition later in the Spring and a brutal final battle that destroyed Chupcan and Suisun resistance.

That expedition, led by Second Lieutenant Gabriel Moraga, included seventeen Spanish soldiers and an auxillary force of mission Indians from San Francisco. On May 22nd, 1810, they attacked the Suisuns and Chupcans, and perhaps others. At least eighteen pagans were taken prisoners and left for dead.

The governor of Alta California wrote a letter to the Viceroy in Mexico telling of the final battle:

Toward the end of the action the surviving [Indians] sealed themselves in three brush houses, from which they made a tenacious defence, wounding the Corporals and two soldiers…After having killed the pagans in two of the grass houses, the Christians set fire to the third grass house, as a means to take the pagans prisoner. But they did not achieve that result, since the valiant Indians died enveloped in flames before they could be taken into custody. The second lieutenant says that he could not reason with the pagans, who died fighting or by burning. There was no room for compassion in this disaster wrought upon them by our troops, because of their resistance.

This Suisun massacre ended the organized resistance of the Chupcans and their Suisun relatives. Most of those Chupcans who converted did so in the year after this battle.

Very likely Mol-le was nearby. She was not among those who went to the mission shortly after. Why? Where did this 73 year old woman go? Who cared for her? The mission records are silent on her husband and children. Her grandson, Jattate, later named Narciso, went into Mission San Jose a full fourteen months after the massacre with a large group of mostly Ompins, who lived in the Pittsburg/Collinsville area. Mol-le followed a year later in June or 1812. She was baptized there about the time many mission Indian children were being baptized and between the mass baptisms of Ompins and Julpuns. Perhaps she had been living with the Ompins.

The record gives detailed information about grandson Jattate’s marriage, the fate of his children and his grandchildren. Grandmother Mol-le died near San Jose’ on the 9th of March, 1816, nearly 80 years old.

When we look at the geneaology of Mol-le’s family, it allows us to describe the dramatic conflicts between Indians and Spanish in terms of real people with real names. It provides a new method of approaching the historical demography of California Indians. It provides a framework for a more complete history of the Chupcans who once lived in harmony with nature in today’s Concord.

Bibliography

Fages, Pedro, A Historical, Political, and Natural Description of California, by Pedro Fages, Soldier, of Spain (Menlo Park: Ballena Press), 1975. Herbert Ingram Priestly, translator

Brown, Alan K., The European Contact of 1772 and Some Late Documentation, in Lowell J. Bean’s Ohlone Past and Present, Native Americans of the San Francisco Bay Region (Menlo Park: Ballena Press), 1994.

Milliken, Randall T., A Time of Little Choice The Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Region 1769-1810 (Novato, Ca. : Ballena Press Publishers’ Service), 1995.

From Bay Miwok Readings, 2003