The Lincoln Era in California and the San Ramon Valley

Introduction

The 1860s were a turbulent time for Americans, as Civil War devastated the country and roiled California politics. California had been part of the country’s fractional debates from its start. When California became the 31st state in 1850, it tilted the number of free states over slave states by 16 to 15.

California was still an unformed frontier region, with San Francisco by far the largest city in the West. California’s white population increased from about 15,000 in 1848 to 380,000 in 1860 which reflected immigrants coming for the great Gold Rush (1848-50), the silver bonanza of 1859 and the state’s many opportunities. Voters had lived in California less than 15 years and opinions on the Constitution, states rights, democracy and slavery reflected life in their original home communities.

California and the Civil War

Debates in Congress and other forums over whether slavery should be expanded into new territories heated up in the 1850s. Zealous abolitionists wanted a complete end to slavery in America while most slave owners thought slavery should have no restrictions. A number of compromises were tried but emotions ran high. Fear of possible slave insurrections was palpable, especially in the many areas where black slaves outnumbered the white population. In 1860 the south had 9,000,000 people, over 3,500,000 of whom were slaves. Northern population was 22,000,000.

The question of whether or not new states should be free, allow slaves, or vote on the issue themselves (Stephen Douglas’s “popular sovereignty”) was a continuing Congressional and public argument. Such debates were exacerbated by the economic, cultural and social differences between North and South.

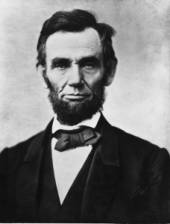

The seven Lincoln-Douglas debates over Illinois’ U.S. Senate seat in 1858 were significant in that they articulated the issue of slavery in America and brought Abraham Lincoln to national prominence. That year Lincoln famously said “A house divided against itself can not stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free.”

During the Presidential election of 1860, southern leaders were primed to secede, even though Abraham Lincoln was a relative moderate on the slave question. Others who had competed for the Republican nomination were far more extreme than he — one reason he was nominated. But clearly the new Republican Party opposed the expansion of slavery into the territories and the era of compromises had come to an end. Southern states began seceding in December, 1860. The Confederate attack on federal Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861 was the spark which began the war.

Union Support in California

California had many southerners who questioned the constitutionality of Lincoln’s opposition to secession and devotion to the Union. The state supported the Union when the Civil War began. California sent regular gold shipments back east, donated generously to the Sanitary Commission (19th century Red Cross) and replaced Union soldiers in the West with thousands of California volunteers. Some Californians also fought in the East.

President Lincoln took several important actions which impacted California. His good friend, Edward D. Baker, led the state campaign for Lincoln in 1860 and later advised him on Pacific Coast issues. Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act (1862) which ultimately brought the transcontinental railroad to California in 1869. And, in 1864, he signed the Yosemite grant, preserving the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Trees for posterity. The Homestead Act which passed in 1862 affected the entire West.

Fighters for the Union

Volunteers from California relieved U.S. regular soldiers throughout the West, freeing them to fight in the east. While the Californians fought no major battles, they guarded wagon trains, fought Indians and tended western forts. These soldiers also saw active combat when they defeated Confederate efforts to drive through New Mexico and Arizona and open a land route to California.

According to Brigadier General Donald E. Mattson, Chief of Military History, California State Military Department: “Per-capita, California provided more troops than any other state in the nation.

In the Bay Area, fortifications on Fort Point and Alcatraz were built to resist possible Confederate invasion by sea. The Camanche, an iron-clad warship, was launched on November 14, 1864, in San Francisco. One of 10 monitors constructed in 1863 in New Jersey, the Camanche was shipped to California in pieces and re-built for use in the Bay. San Francisco subsidized the building of what they called “our monitor” as the Civil War drew to a close and viewed themselves as integral to the war effort.

Joseph Wilkes, a 17-year old from the Tassajara Valley, enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1863 and was assigned to Company K, 6th Infantry, California Volunteers. This was particularly interesting since his father Albert Gallatin Wilkes was a strong Democrat and did not support Lincoln’s efforts to preserve the Union. The family came from the slave state of Missouri and two of Albert’s brothers fought for the Confederacy. Joseph was served in the military for two years and helped guard the gold shipments which were sent east in support of the Union.

Volunteers went east at their own expense to fight under the Massachusetts and other flags. One group was called the “California 100” with a banner, or guidon, which showed a grizzly bear. Ultimately, a total of 500 “California 100” troops participated in more than fifty Civil War engagements from Charleston to Appomattox.

In addition, Union Colonel Edward D. Baker led another California and Oregon Regiment (part of a Philadelphia Brigade) until his death at Ball’s Bluff October 22, 1861. These soldiers received little credit as Californians for their service, but they were known to have been good fighters who helped withstand the brunt of Confederate General Pickett’s charge during the Battle of Gettysburg.

“…all of a sudden it became a hand-to-hand affair. It was soon evident to (Captain J. Sewall) Reed that he was in for a whipping, and his men began breaking through the fences and into the field, but fighting all the while. His Californians, especially notoriously good fighters, were standing up to the rack like men, dealing out to us the best they had. They rallied at every call on them and went down with banners flying.”

-John W. Munson, Commenting on the California 100 (Company A, Second Massachusetts Cavalry) from Reminiscences of a Mosby Guerrilla.

Thomas Starr King Spoke for the Union

The charismatic Unitarian minister and orator T. Starr King spoke for the Union and raised funds for the Sanitary Commission in speeches throughout California. In the early 1860s, Californians took widely diverse positions. Some supported an independent nation on the Pacific Coast, others argued for secession, and King ardently crusaded for the Union.

He could be flowery. For example, he met general approval when he pronounced that the Confederates “with their traitorous cannon and unblessed steel…are fighting against God” and compared Northern California’s Copperheads to Judas Iscariot: “Follow them if you would give comfort to the enemy…Follow them if you would listen to the music of silver that will turn all America from its true destiny into a field of blood.”

The precursor of today’s Red Cross, the U. S. Sanitary Commission took care of wounded soldiers during the Civil War. It gave women the chance to help the war effort on the battle field and in hospitals where, given the primitive medical knowledge at the time, even minor wounds were often fatal. A devastating 620,000 died in the Civil War, leaving practically no family untouched. Casualties amounted to over one million.

In November of 1862, Starr King spoke at a huge rally at Contra Costa County’s Pacheco giving his speech, “The New Call of Patriotism.” He urged Sanitary Commission support: “Give, give I pray you. There are no enemies in the hospital or the grave.” A letter from Russell Swain, describing King’s speech, stated “men became frantic with enthusiasm and loyalty.”

People supported the Sanitary Commission as a way to help the troops. Rallies throughout California raised funds, with many San Ramon Valley donors’ names published in the Gazette. California contributed an astonishing twenty-five percent of all funds raised for the Commission, the most of any state.

The San Ramon Valley

From 1861 to 1865

The San Ramon Valley produced cattle, hay and grain cultivation during the sixties and beyond. The villages of San Ramon, Danville and Alamo were small, with resident hotels, black smithies and general stores. Only Alamo and Danville had post offices. In 1862 ranchers had to cope with 49 inches of rain and huge floods which tore out the bridges, followed by two years of a devastating drought with less than 10 inches of rain. State-wide these weather variations mark the end of livestock grazing’s dominance and the beginning of grains as California’s main agricultural products.

In addition, land titles in Alamo and Danville had not yet been settled, debates over secure ownership were still in the courts, and the final patent for the north part of the San Ramon Valley wasn’t signed until the 1870s. Jose Maria Amador’s rancho title had been concluded, settling San Ramon land south of today’s Crow Canyon Road. This patent was signed by President Lincoln on March 7, 1862.

Some grammar schools had been constructed. The valley’s pride was the Union Academy, a three-story boarding high school on the border of Alamo and Danville. It opened in 1859 and was the first high school in the entire County. The building hosted large meetings, church services and school classes, with rooms for boarding students. A fire during the summer destroyed the building in 1868.

In Contra Costa County there were some hot political disputes which were recorded in the weekly Contra Costa Gazette. A Contra Costa Guard which opposed secessionists in the County was formed in September 1861and was part of the First Cavalry Regiment, Second Brigade of the California Militia. Sixty-three men signed up.

James Smith recalled a political rally in Pacheco at the fair grounds, probably around 1861. He mentions prominent San Ramon Valley Democrats John Snydor, Jesse Bowles and Dan and Andrew Inman. Bowles organized a parade from Danville which featured a large log with the name “Constitution” painted on each side. Loaded on a wagon, the log had a huge maul with the word “Lincoln” printed on it. Smith wrote “This was to indicate that Lincoln was driving his advisors to split the Constitution of the United States.”

Many in the San Ramon Valley were from the southern states of Kentucky and Tennessee and the slave state of Missouri, while others hailed from Massachusetts, Illinois and points north.

Slavery in California and the County

The debate about slavery in new states focused on California soon after the Gold Rush. With a substantial population — and some politicians eager to be

U. S. Senators — Californians skipped the Territorial stage of government entirely. The 1849 Constitutional Convention had one section which forbade slavery in the new state, stating “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, unless for the punishment of crimes, shall ever be tolerated in this State.” Miners were a major voice for a free state since they objected to owners bringing their slaves to work the mines.

The issue of whether or not slaves became free when they traveled to a free state was one which federal laws covered. Slavery existed in California for years; there were even slave auctions in Sacramento. The California Fugitive Slave law in 1852 mandated that runaway slaves must be returned to their masters which re-enforced the concept that African-Americans were property, even in a “free” state.

Freed blacks came to the Gold Rush and many enslaved blacks worked to pay for their freedom in California. They also raised funds to free their families in the south. Nevertheless, it was clear that freed blacks were not viewed as equals in California. In this era they were unable to vote, testify in court or send their children to public schools. Slaves or “servants” in California and the nation were finely freed when the 13th Amendment was passed in 1865. After successful lobbying in Sacramento, the right for California blacks to testify in court was passed in 1872 and segregated schools for blacks were ended in 1880.

Early Contra Costa County histories don’t discuss blacks, but the census reveals that some settlers brought black slaves or servants to the area. In Contra Costa’s San Ramon Valley, the 1860 census for Township Two (Lafayette/Alamo-SRV) counted eight black people. The County had 5,328 people including 27 “free colored.” The state population was 380,000 in 1860 and listed 2,500 black people. We have information about three of them in the San Ramon and Tassajara Valleys

Both the Albert Wilkes and Andrew Inman families listed a black in their household in 1860 and both were active Democrats from slave states. The Wilkes family had moved to a ranch on Finley Road in 1856 and provided land for the first Tassajara School. The 1860 census listed a 14-year old black girl, Susan Wilkes. One source describing the Tassajara Valley stated that slaves were buried “on the hill off Finley Road and just north of Camino Tassajara.”

Andrew Inman married Ann Young and brought her mother “Aunt Sallie” Young to live with them. According to the 1860 census, their household included Jane Young, age 50, a black house servant.

A free black called Mack (Jasper) was mentioned twice by James D. Smith in his memoirs. He recalled an early July Fourth celebration:

“A barbecue of beef and mutton was prepared by a negro we knew only as Mack, an expert cook, who had come from the southern slave states with Boyd and Field who first occupied Green Valley in 1850 with a drove of American cattle. Mack was free, and he located where Alamo was later built, among the Spaniards, and was the first shoemaker or repairer in all that section.”

According to Smith, Mack also barbequed at religious camp meetings in Alamo during the 1850s. As a growing boy in those years, Smith tended to remember food.

When President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863, it freed slaves only in the seceding states. However, the Proclamation set the path for total emancipation in the country. On January 31, 1865, after intense lobbying by Lincoln, Congress passed the 13th Amendment to the Constitution which abolished slavery nation-wide. The final state ratified the Amendment on December 6, 1865.

Two Pairs of Democratic Brothers called for “Liberty First, then the Union”

Two early settlers, brothers Daniel and Andrew Inman, were important leaders in the community. They lived and ranched in Green Valley where Andrew had donated the land for the first Green Valley Grammar School. Andrew represented the County in the State Assembly in 1856 and the State Senate from 1860 to 62.

Daniel Inman, a lifelong Democrat, was also interested in politics and was respected as a man of probity and generosity. The town was named for him in 1858 after he bought 400 acres along today’s Diablo Road and Front Street. In 1863, he married Josephine Jones of Alamo, who was born in California after her parents (John M. and Mary Ann Jones) had traveled over the Sierras in 1846.

Andrew and Dan Inman appeared regularly in Democratic Party and Democratic County Convention reports in various Contra Costa Gazettes. In 1863, Dan was nominated by the County Democratic Convention and ran for Sheriff. But it was the middle of the Civil War and Republicans, called the Union Party then, made the election case that to vote Democrat would be disloyal. He lost the election to J. J. McEwen, 1006 to 528 on September 2, 1863.

Another set of Democratic brothers, John M. Jones, and his older brother Nathaniel, lived in Alamo and Lafayette, John M. and Mary Ann Jones had moved to Alamo in 1851 with their family and he was an active Democrat. He was the first Alamo postmaster and held several other County posts. In the September 2, 1863 election he ran for Assessor as a Democrat and lost 1009 to 515.

Nathaniel Jones, the County’s first sheriff and a County Supervisor, adamantly opposed the Lincoln administration which he felt had betrayed the U.S. Constitution and was responsible for the war’s enormous carnage. County Democratic Conventions in the sixties expressed these sentiments which were often articulated by Nathaniel. The convention in April 30, 1864, stated that the Emancipation Proclamation meant “the subjugation of the southern States to the condition of colonial dependencies, which would be alike incompatible with free Government and revolting to the national will.”

The Convention’s resolution also pointed out: “the rebellion of 1861 having merged into a war of frightful proportions is rapidly undermining the fair fabric of our institutions and exerting a baleful influence on human civilization. “

(Contra Costa Gazette, May 14, 1864)

Other valley Democrats included August Hemme, William Norris, Albert G. Wilkes, Felix Coats, Golder Field, Van Hayes, Edward Sturgeon, and Jesse Bowles.

Republicans Stood for Lincoln and the Union

Republicans in the valley supported Lincoln and the Union and raised funds for the Sanitary Commission. E. H. Cox, who hailed from Indiana and was the father-in-law of R. O. Baldwin and William Meese, chaired the County’s Union Republican Convention in 1864. A huge Union rally was held in Danville in Flournoy’s field (around today’s Danville Oak) in 1864, which was covered extensively by the Gazette.

David Glass was a County delegate to the Republican State Convention in 1864, pledged to Lincoln. Family lore says that, after Lincoln was elected in 1860, Glass left the Democratic Party and became a Republican, setting the party affiliation for Glass descendents from then on.

When Charles and Cynthia Wood moved to Sycamore Valley in 1862, daughter Charlotte later wrote: “It being early Civil War times, there were many sympathizers with both the North and the South, and naturally there was a little hesitancy in meeting new comers, so no one called on Mother during her first six months here.” The Woods were “strong Northerners” who had originally emigrated from Massachusetts.

Lincoln and Johnson Club members from the valley in 1864 included Glass, Charles Howard, James Foster, J. R. McDonald (Club President) and A. W. Hammett. Other active south county Republicans were the Crows, Levi and Sarah Maxcy, Henry Hawxhurst and R. G. Davis.

The Question of a Flag

Not far from the Woods’ ranch, in eastern Sycamore Valley area, two families took different sides — the Maxcys from Massachusetts and the Coats from Missouri and Arkansas. Sarah Maxcy was an avid abolitionist and Union supporter who proudly flew the American flag in her yard, to make clear her position.

Here is a story about the Maxcys and the Coats during the war written by Vivian Coats Edmonston from family memories.

“Sarah was as firm an abolitionist as there was to be found in the Sycamore Valley. Legend has it that a group of young fellows of the neighborhood (another version says they were Coats boys) called on her one day with a request that she desist from flaunting the stars and stripes from the flag pole in the yard.

“They were so incautious as to suggest that they were prepared to remove the flag by violent means, if necessary. She resented the intrusion as well as the demand and, since she backed her resentment with a rifle, the boys reconsidered, happily without bloodshed.”

Sarah Maxcy is represented here by a picture of Annie Oakley in her later years.

July Fourth Memories

The Fourth of July in 1864 also provided some memorable moments related to the Civil War as well, again from Smith’s Recollections:

“The third Fourth of July celebration I know of was held at Danville in 1864. I did not attend as my father was very ill and I was his nurse, but I knew of the extensive preparations. It was war time, and there was great excitement and much feeling between the Democrats and Republicans. San Ramon at that time was numerically Democrat.

“Great preparations had taken place, speakers engaged and a chorus of singers had been chosen. I recall James Hardy, a workman in the carriage shop at Danville, had his singers practicing for over a week before. I had been spoken to as a reader of the Declaration of Independence, but could not attend and Finis E. Johnson, Preacher Johnson’s son and my classmate at Union Academy in San Ramon, was selected and he immediately began to read and commit the Declaration to memory.

“I learned that there was a large assemblage, a speaker’s stand and seats had been prepared just at the locality where the San Ramon Valley High School is now located. Of course, there were many Republicans as well as Democrats in the assemblage. There was a family name Crow who lived in what was known as Crow Canyon on the road from San Ramon to Hayward. This family had been known to have very decided political opinions, strongly Republican. There was, besides the father, Jep, Granville, John, Francis and William Crow.

“When the people had assembled, Mr. Hardy with his singers sang several patriotic songs, and the chairman called for the reading of the Declaration of Independence. As before stated, Finis Johnson had memorized the Declaration, and he came forward and began to recite. He had not proceeded far until one of the Crow family arose and in forceful language asserted “No secession speech shall be delivered here” and followed with more strong language.

“Great excitement at once prevailed. Some women screamed. All the Crows flocked together, and for a short time there was great excitement that resulted in the meeting being broken up. Family rushed to their conveyances and started for their homes. I learned the facts immediately after the adjournment. Some of my friends came to my home to tell me.”

The Contra Costa Gazette wrote up this event too, saying at one point “All is excitement and confusion. Women screaming, children crying, dogs barking, men and boys running hither and thither.” And ending the article: “..let the cry go forth that there is yet in San Ramon valley enough patriots to protect themselves from insult, and protect the institutions for our Government from being vilified by travelling one horse secesh politicians.” (July 16, 1864)

Political Rallies

Prominent leaders in the valley definitely were on different sides. Who knows how the conversations went when they met? Many on both sides did not want to see brother fighting brother, which happened repeatedly as the war progressed. But the issue of slavery in America had been avoided for the most part by the Founding Fathers in an effort to bring the 13 colonies together. And it festered like a canker in the decades that followed.

The October 8, 1864, Contra Costa Gazette covered one rally in Danville under the title The Union Gathering:

“The largest and most respectably attended meeting ever witnessed in San Ramon Valley, was held on Saturday, October 1st, under the shady oaks in the field adjoining the residence of Thomas Flournoy, Esq., by the union party of Contra Costa county. Hon. J. F. Swift, first addressed the meeting, who gave the assemblage to understand that nothing but the re-election of Lincoln and Johnson would satisfy the majority of all thinking men. He was followed by hon. Frank Pixley, who gave one of his good sound sense speeches, which made some of the Democratic worshippers pull long faces, and the meeting broke up with three cheers for Lincoln and Johnson. The Union League made an excellent appearance with their fife and drum, and starry banners, and were loudly cheered. DANVILLE.”

Since Danville was a hotbed of Democratic support, the Republicans may have set up this rally to get in their opponents’ faces.

Presidential politics in 1864

Most state officials were Democrats at the war’s start. In fact, in 1860 Abraham Lincoln took California by just over one-third of the total vote. He won the election largely because the Democratic Party had two candidates, Stephen Douglas and John Breckinridge. But, during the war years, Union Republicans held sway in California and, in 1864, the Lincoln/Johnson ticket easily defeated McClellan/Pendleton in the state.

The Presidential election of November, 1864, showed south County’s Democratic sentiments. The Danville precinct — which probably included San Ramon — supported George McClellan over Lincoln. Perhaps one sees the Inmans’ hands in this.

This cartoon has Lincoln saying “I have a little joke,” referring both to McClellan’s height and experience.

The Contra County Gazette, Nov. 12, 1864, reported:

THE ELECTION IN CONTRA COSTA. — The following table shows the number of votes in each precinct for the Union and for the Democratic ticket:

Lincoln McClellan

Alamo 50 17

Danville (SR) 76 91

Moraga 24 39

Martinez 89 24

Antioch 133 92

(plus others)

—————————————————————————

County Total 958 523

And later in this long article:

“When we look at the separate precincts we find that Moraga and Danville were the only ones where McClellan got a majority over Lincoln. In each of these two precincts this majority was 15. In Martinez Lincoln’s majority was nearly four to one, in Pacheco over three to one, in Pinole nearly three to one, in Clayton slightly more than three to one, in Alamo almost three to one, and in Nortonville among the coal miners more than sixteen to one. In San Pablo, Antioch and Somersville also there were large majorities for Lincoln over McClellan, although not so large as in the precincts just named.”

“On the whole, the Union Party has great cause for rejoicing at the result of the election in our county and the same happy state of things seems to exist throughout nearly all the State, so much so that it is probable the total majority for Lincoln in California will exceed twenty thousand votes.

“So far as we have learned, the day of election was a model of good order, sobriety and quite throughout the whole county. In Martinez and Pacheco it was more like Sunday than a common week day. In Pacheco all the saloons were voluntarily closed, thus setting an honorable example of forbearance and patriotism that deserves special honor.”

“Any feelings of bitterness that may anywhere have sprung up were wisely held in check and controlled by the praiseworthy desire of devoting the day wholly to the discharge of its hold duties and to the exercise of the sacred rights of American freemen, in a manner to do honor to their name.”

War Ends and the President Is Killed

Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865, marking the end of the great conflict. It had lasted 4 years with the loss of 620,000 lives. Grant offered generous terms to the rebels, in accordance with President Lincoln’s wishes, and sent them home with their horses and small arms.

This painting by Thomas Lovell records the Appomattox surrender

Less than a week later, on April 14, John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Lincoln. Northern leaders, charging that Booth’s mad act was a murder by Jefferson Davis’ agents, characterized it as part and parcel of the dying Confederate war effort.

The country grieved as Lincoln’s funeral train traveled slowly to Springfield via New York and Chicago and was viewed by millions of people. Small groups of mourners gathered and bowed their heads as the train went though the countryside carrying “Father Abraham.” Lincoln’s plans for forgiveness and national reconciliation were left to others more interested in retribution.

Historian Bruce Catton: “As the war ended, they (citizens) had come to understand his greatness; and now, when he was struck down at the very moment of his triumph, they felt an anger so black that Lincoln’s own vision was blotted out.”

A soldier of the ”California 100” from Sacramento, Samuel Corbett, had been present at Appomattox. In his diary for April 16, 1865, he wrote:

“It was confirmed this afternoon, he was assassinated. Every man in the army feels as though he had lost a Friend. It seems so hard that just as the war ended he should be killed…We will hope Mr. Johnstin will be his avenger and treat these Rebels as they deserve.”

Memories of Lincoln

A year later, the loss of Lincoln was remembered in California’s San Ramon Valley during a Green Valley School picnic as reported in the Gazette.

San Ramon Valley May 7, 1866

“The following lines,on the death of Lincoln were recited by Master Frank Smith, with an earnestness of feeling and correct enunciation, which indicated an appreciation and careful study of his subject:

The pines are green on Shasta

No palm-tree leaf is here,

But a noble oak has fallen

In the spring time of the year.

You may journey to the sunset

And from the summit to the sea,

But you will find not in the forest

So stout, so brave a tree.

It stood the wrath of winter

The blinding sleet and snow;

But now the ax of Treason

Has laid that good tree low.

Rest, Lincoln in thy glory

Yet slain by stealth ye die,

Up yonder, amongst the stars

They ask not — but why? “

Contra Costa Gazette, edition of May 19, 1866

Conclusion

Lincoln has had more books written about him than any other figure except for Jesus Christ. The accomplishments of this self-made man, rising from America’s frontier to the Presidency, are legion and our fascination with him never seems to end.

“Some men stand still, amazed, when the tempest darkens around them; others grow and rise to the height of the occasion; but few have ever grown and risen as did this man; his mind maturing and his views expanding under the stirring of his times.” Robert Dale Owen, Reformer and Indiana Congressman, 1870

In Team of Rivals Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote: “His conviction that we are one nation, indivisible…led to the rebirth of a union free of slavery. And he expressed this conviction in a language of enduring clarity and beauty, exhibiting a literary genius to match his political genius.”

At the conflict’s end, thousands of war-weary, dislocated Easterners looked for new opportunities and moved to California. The state population swelled from around 380,000 in 1860 to 560,000 in 1870, helped by the newly completed transcontinental railroad. Over 100 Civil War veterans moved into the Tri-Valley, from Alamo to Livermore.

March 22, 2010

Beverly Lane

Museum of the San Ramon Valley, Danville, California

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Lincoln Era in California and the San Ramon Valley

Bastin, Donald E., Rebels at the Gate: Civil War San Francisco and the Confederate Sea-Borne Threat, Hayward: M.A. Thesis at California State University, 2001

Bean, Walton and James J. Rawls, California, An Interpretive History, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983

Catton, Bruce, The Civil War, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1987

Cleland, Robert Glass, A History of California, From Wilderness to Empire, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1959

Contra Costa Gazette, 1860s (From the CCC History Center)

Donald, David Herbert, Lincoln, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995

Edmonston, Vivian Coats, Edmonston Notebooks at the Museum of the San Ramon Valley

Goodwin, Doris Kearns, Team of Rivals, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005

Henig, Gerald S. and Eric Niderost, A Nation Transformed, How the Civil War Changed America Forever, Nashville, Tenn.: Cumberland House, 2007

Katcher, Philip, Battle History of the Civil War 1861-1865, New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2000

Mero, Bill, Snakes in the Grass: Copperheads in Contra Costa County. On CCC Historical Society web site

Moore, Shirley Ann Wilson, “”We Feel the Want of Protection’: The Politics of Law and Race in California, 1848-1878,” pp. 96-125, California History Magazine, Taming the Elephant: Politics, Government, and Law in Pioneer California, Vol. 81 No. 3/4, 2003

Munro-Fraser, J. P., History of Contra Costa County California, San Francisco: W. A. Slocum & Co., 1882, reprinted 1974 (see N. Jones biography)

National Park Service, Appomattox Court House, National Historical Park, Virginia, Handbook No. 160

Nemir, Claudia Mauzy interview about David Glass, 2009

Posner, Russell M., “Thomas Starr King and the Mercy Million,” The California Historical Society Quarterly, Dec. 1964, pp. 291-307 (Includes the Russell Swain letter)

Rogers, Larry and Keith Rogers, Their Horses Climbed Trees, A chronicle of the California 100 and Battalion in the Civil War, from San Francisco to Appomattox, Atglen, PA: Schiffer Military History, 2001

Rolle, Andrew F., California, A History, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1967

Smith, Prof. James Dale, Recollections, Early Life in the San Ramon Valley, ed. G. B. Drummond, Oakland, CA: GRT Book Printing, 1995

Starr, Kevin, Americans and the California Dream 1850-1915, New York: Oxford University Press, 1973

Wood, Charlotte E, Rambling Reminiscences of The Charles Wood Family and Their “Woodside Farm” Home, Aug. 1951, p. 4