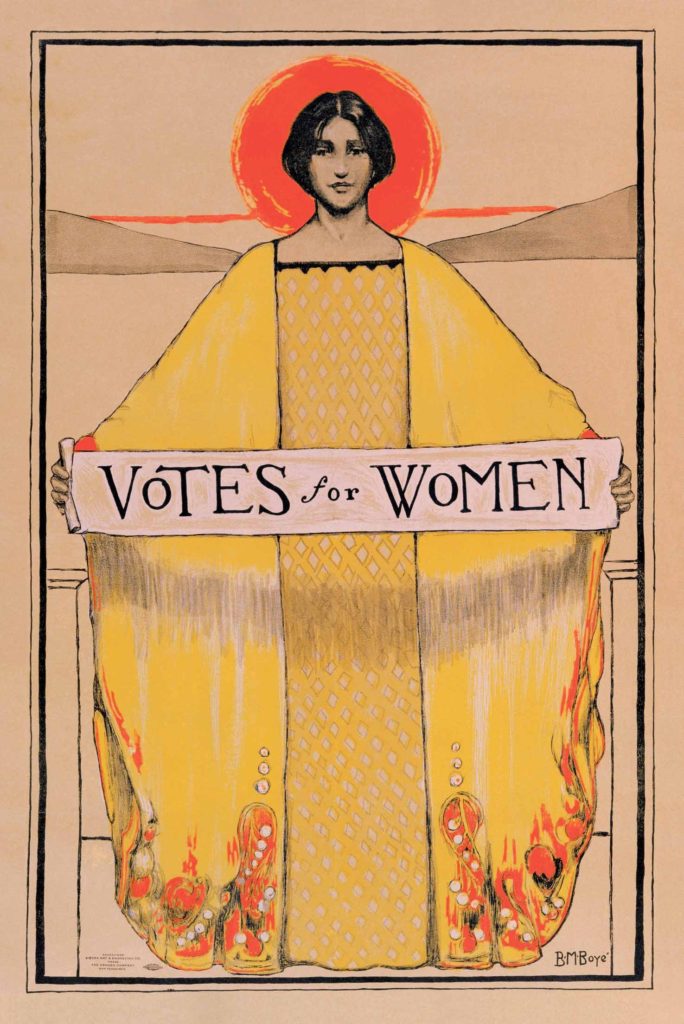

Woman Suffrage First Appeared on the California Ballot in 1896

By Beverly Lane

In the first California constitution of 1849, women did win some property rights which reflected the state’s Spanish legal traditions. Many transplanted Easterners objected to such rights, feeling it threatened the superiority of husbands. Others thought such rights might bring women of property to the state.

Other lobbying by women changed state law to allow women admission to the bar as attorneys (1878) and to pursue “any lawful business, vocation or profession,” including medicine. (1879)

In 1874 the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was organized to combat liquor interests. Often women and children suffered from abuse by drunken husbands or fathers and had no recourse in law. The organization grew rapidly and many of their numbers proudly supported woman suffrage.

The Liquor Dealers League in San Francisco was alarmed about the connections between the WCTU and suffrage advocates. According to Mae Silver, the League included “the producers, proprietors and patrons of drink” and was especially powerful in San Francisco. In 1896 the City included 25% of the state’s voters.

Eastern suffragists helped with the 1896 campaign. The indomitable organizer Susan B. Anthony spoke in favor of Ballot No. 6 at meetings throughout the state including one in Martinez chaired by educator John Swett. Miss Anthony spoke about the many advances which women had made in the past fifty years. The October 10 Contra Costa Gazette stated: “Her speech throughout was well received and most heartily applauded at the close.”

A correspondent from Danville wrote this on October 10,1896: “Women suffragists seem to have met with rather a cold reception in this vicinity…which leads us to believe that our women are satisfied that their condition cannot be improved by a change, and they might not have so good a time as at present.”

It was a large state and many more resources were needed to make the women’s case. In the Bay Area, San Francisco, Alameda and Contra Costa County voters opposed woman suffrage at the November election. Contra Costa’s tally was 1638 against and 1002 in favor. The results in the San Ramon Valley were:

| Yes | No | |

| Alamo | 27 | 25 |

| Danville | 45 | 72 |

| San Ramon | 38 | 32 |

| Tassajara | 21 | 29 |

| Walnut Creek | 48 | 45 |

Clearly California voters were not ready to take the step. The Contra Costa Gazette reported that women met almost immediately to analyze the vote. One article stated that the vote “showed that with a little more time and work we would have carried this county.” They rolled up their sleeves and began to plan for another effort.

Sources

Contra Costa Gazette, October 10, November 21, 1896

Elinson, Elaine and Stan Yogi, Wherever There’s a Fight, How Runaway Slaves, Suffragists, Immigrants, Strikers, and Poets Shaped Civil Liberties in California, Berkeley, California: Heyday Books, 2009.

Silver, Mae, Women Claim the Vote in California, from FoundSF, 1995