Remembering the Valley’s First People

By Beverly Lane

In past years, we have been reminded about the first people who lived in the San Ramon Valley as Indian burials has been unearthed in Alamo along the creek and Danville at San Ramon Valley High School. People are very interested in these finds and want to know more about these people. What tribe did they belong to? How long ago did they live here?

From archaeological digs and carbon dating, we know that people lived in the San Ramon Valley for at least 5000 years, possibly much longer. Discoveries in Alamo when the I680 freeway was excavated, in Danville by the Old Oak, and in East County when the Contra Costa Water District expanded the Los Vaqueros reservoir have all yielded fascinating finds.

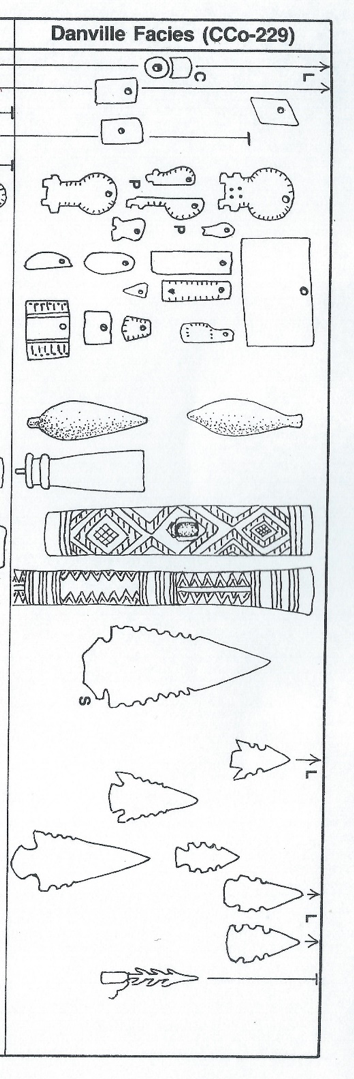

CCo -229

A Smithsonian reference book edited by Robert F. Heizer, The Handbook of North American Indians, California, provides excellent information about the Bay Area’s early settlers. One page shows drawings of artifacts found in Danville during the 1950s at CCo-229 (the site-specific number). Beads, abalone ornaments, charmstones, spear and arrow points, deer bone awls, pestles, mortars and bone whistles are shown. Examples of these items are currently on display at the Museum of the San Ramon Valley, donated to the museum by individuals over many years.

Items from CCo-229, Vol. 8 California, p. 44, Handbook of North American Indians

When Brazil poured the topsoil out, two stone artifacts were found which Cozens retrieved. One was a nicely formed, broken pestle about four inches long. It would have been used to pound seeds or acorns in a stone mortar. Another was a charmstone, again nicely formed. While we don’t know the precise purposes of these charmstones, Alfred Kroeber, Robert Heizer and other ethnohistorians believe the charmstones had a variety of sacred purposes, promoted fertility, or provided good luck in hunting or fishing.

CCo 308

When the state realigned San Ramon Creek in Alamo to construct the I680 freeway, the archaeological evidence unearthed in 1962 (CCo-308) was significant for several reasons. Dr. David Fredrickson was one of the first California archaeologists to reach out to Indian descendants and confer with them about the remains found at such sites. At CCo-308 he uncovered three distinct levels of occupation and was able to date the site’s lowest strata to over 5000 years ago. The dig and its findings were viewed as one of the most important in the Bay Area at the time.

Although the freeway construction schedule limited the time allowed, Fredrickson noted that there would have been more to learn in the layers below and may have revealed settlements up to 10,000 years old. The dig was financed by the Archeological Salvage Program of the State of California’s Division of Highways.

The Valley’s First People

Around 250 years ago several tribes lived in the San Ramon Valley. Theirs was an ancient culture with intimate knowledge of the land passed down in an oral tradition. One tribe, called by the Spanish the Tatcan, lived in the drainage area of the San Ramon Creek watershed which flowed north. They belonged to the Bay Miwok linguistic group.

Other tribes, the Seunen and Souyen, lived in San Ramon and Dublin. Their territory included the Alamo, Tassajara and South San Ramon Creeks which flowed south into a vast marsh area. They spoke an Ohlone (also called Costanoan) language. The Bay Miwok and Ohlone linguistic areas appear to have met around today’s Norris Canyon Road. Randy Milliken’s mission records research revealed marriages between members of these tribes.

Each tribe had as many as three villages of 50 to 250 people, with perhaps several hundred Indians living in the valley at western contact in 1772. They moved from permanent settlements to other camps during the year. At least seasonally, Indians lived on the Mount Diablo foothills, as evidenced by bedrock mortars found there.

Their lives revolved around the rhythms of the natural world, called “seasonal rounds” Their diet was dependable and diverse and included seeds, acorns, fish, birds, insects, animals and root plants. In certain seasons, such as the autumn acorn-gathering, people worked from dawn to dusk; at other times of the year, life took a more measured pace.

Many archaelogical finds with different site numbers are scattered throughout the San Ramon Creek watershed. Most of the items discovered are stored at Sonoma State University. However, the museum does have several artifacts found in valley locations from Alamo to San Ramon.

Each September the Museum of the San Ramon Valley mounts a special Indian Life exhibit and provides reference books in the research library with extensive information about California Indians. On school day mornings, fourth graders learn about the Indians who lived in this place from trained docents.

Sources: Robert F. Heizer (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians, California (Vol. 8) 1978; Malcolm Margolin, The Ohlone Way; Randy Milliken, A Time of Little Choice The Distintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area 1769-1810; Alfred L. Kroeber, Indians of California, 1925; Beverly Ortiz, Ohlone Curriculum 2015 (see ebparks.org, educational resources)