The Bay Miwok Language and Land

Randall Milliken Time of Little Choice, p. 219

In 1769 when the Spanish first came to California in force, they found a native population estimated at 340,000 people. California was very densely populated and was isolated in many ways. The languages the people spoke were incredibly diverse — an estimated 100 languages with many dialects within each.

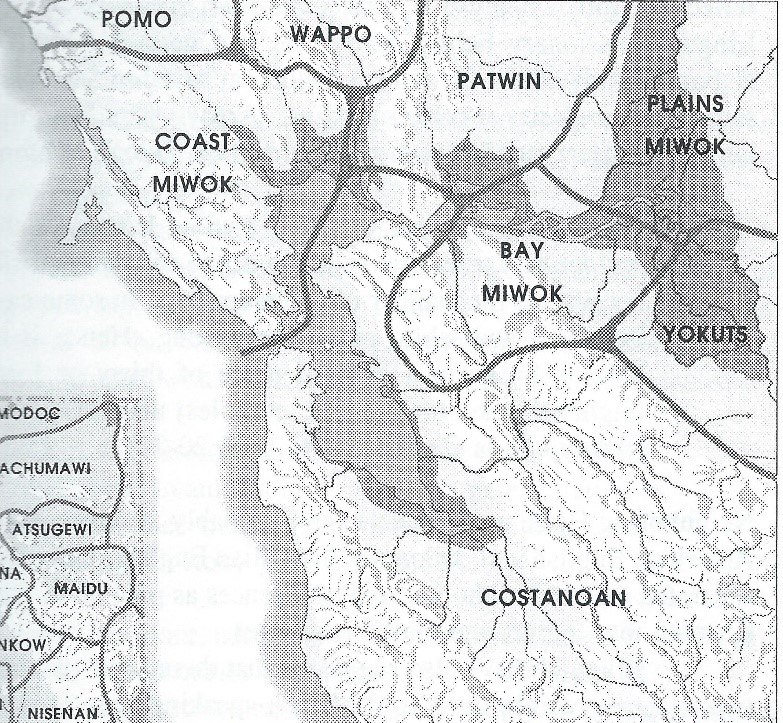

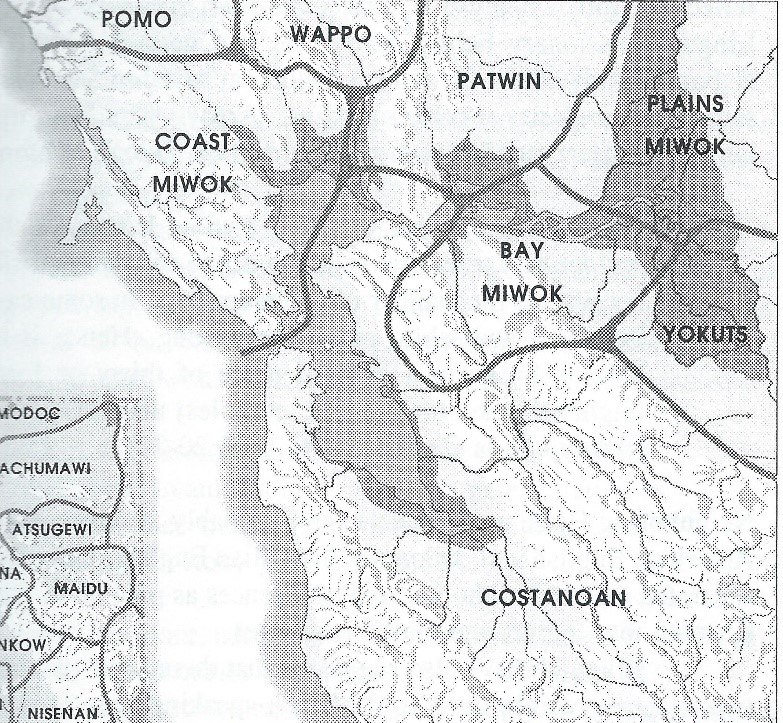

Bay Miwok Indian tribes lived in central and eastern Contra Costa County. These tribes were named Chupcan, Julpun, Ompin, Saclan, Tatcan and Volvon by the Spanish who recorded these names in the Bay Area mission baptism, marriage and death registers. The San Francisco Bay Area included these linguistic groups: Coast and Bay Miwok, Ohlone/Costanoan, Patwin, Wappo and Yokuts.

As early as 1821 Father Arroyo de la Cuesta of San Juan Bautista recorded a Saclan vocabulary which he wrote was demonstrably different from the Costanoan language used in the rest of the East Bay. The Saclan language was described by later researchers as close to Plains Miwok.

According to linguist Catherine A. Callaghan, Miwok is a family of seven genetically related languages spoken in Central California. They descend from a language spoken about 2500 years ago, which is called “Proto Miwok.” She cites a similar, more familiar example, the Romance family of languages; these include French, Spanish, Italian, Romanian, etc.

The Miwok family consists of the Western Miwok languages (Lake and Coast) and the Eastern languages (Bay, Plains, Northern Sierra, Central Sierra and Southern Sierra). According to Dr. Callaghan “these languages were about as far apart as members of the Germanic family, and they are not mutually intelligible.” Probably many Indians were bilingual or multi-lingual.

The Bay Miwok and Their Territories

The Bay Miwok tribes each had one to five semi-permanent villages and numerous temporary camping sites within a fixed territory of about 6 to 10 miles in diameter. Each tribe knew its land and boundaries intimately and owned the land communally. They probably lived within different watersheds, consumed seasonal foods such as acorns, seeds and salmon and took advantage of their proximity to waterways. The Bay Miwok tribes each ranged in numbers from 200-500 at the time of European contact, according to ethnohistorian Randall Milliken.

Periodically tribes met with others to trade. Autumn gatherings on Mt. Diablo included opportunities to visit, trade, find marriage partners and dance. Anthropologist Robert Heizer wrote “we must keep in mind the extraordinary localism of California Indians…An ordinary person in his whole life probably did not travel more than 10 or 15 miles away from the spot where he was born, lived, would die, and be buried.”

Chupcan was the name given to the Indians who lived in the Diablo Valley along the Suisun Bay. Chupcan homelands probably included Concord, Pleasant Hill, modern Bay Point, Naval Weapons Station Concord, Clyde, Pacheco, part of Walnut Creek and several of the islands in Suisun Bay. Initially they encountered the Fages-Crespi expedition in 1772 and the Anza troops in 1776. The main Chupcan village was quite large and was described by Pedro Fages as comparable to the largest villages he saw in California, according to historian Dean McLeod.

The Chupcan were a river people and, when Spanish troops invaded their territory in 1805 to retrieve mission fugitives, the Indians fled across the water and settled with Suisun relatives in Solano County. That year a marsh in Chupcan territory was named “Monte del Diablo,” probably because the Indian escape made the Spanish troops think the devil had helped them get away. By 1806 21 Chupcan had joined the missions. According to Randall Milliken, by 1815 a total of 151 Chupcan appeared in mission baptismal records.

Julpun

Identified in Father Narciso Duran’s topographical map in 1824, the Julpun lived in the northeastern corner of the East Bay, probably including present-day Oakley, Brentwood and some of Antioch. Thus, their land included the confluence of the San Joaquin River and lower Marsh Creek. Initially many of them moved eastward and northward into the delta rather than submit to the mission system. A few went to Mission Dolores in 1806 and Mission San Jose from 1806-1808, with 108 more entering Mission San Jose by 1813. Milliken lists a total of 141 Julpuns baptized by 1819.

John Marsh bought his Rancho Los Meganos from Jose Noriega in 1837, an area which included the Julpun’s territory; he called the Indians there “Pulpunes.” Julpuns may have returned to their homeland to work for Marsh after Mission San Jose was secularized in 1836.

Ompin

Also listed on the 1824 map, the Ompin had a village north of the Sacramento and San Joaquin River around today’s Collinsville. Their territory probably included the north and south side of the river (present-day Pittsburg) and the islands in between. In such a position they would have controlled the entrance to these important rivers. A few went to Mission Dolores with the Chupcan in 1810 but most went to Mission San Jose with the Julpuns – 78 in 1811 and 15 in 1812. A total of 95 mission baptisms are listed (Milliken).

Saclan

This tribe lived in the inland valleys east of the East Bay hills including present-day Moraga, Orinda, Lafayette, Briones Regional Park and Walnut Creek. Saclan were first identified in the Mission San Francisco records in 1794-5 when 143 people were baptized. A serious drought may have been the reason they (and several hundred others) came to the mission. Once baptized, the missionaries expected the converts to stay at the mission and to leave only with permission. But this influx of converts overwhelmed the missionaries’ ability to house and feed them and an epidemic (probably typhus) caused many of them to return to their homelands.

Saclan were identified as the leaders in a major East Bay rebellion of Indians. They killed the Christian Indians sent to get them and resisted the Spanish troops who came after them in five expeditions from 1795 to 1805. The Spanish may have used the name “Saclan” to include other Bay Miwoks in their mission records and accounts of battles. By 1810, 171 entered the missions, according to Milliken.

Tatcan

The Tatcan lived on the west side of Mt. Diablo in the watersheds of the San Ramon Creek. This area included modern day Danville, Alamo and parts of San Ramon and perhaps Walnut Creek. While a few went to Mission Dolores in 1794 with Saclan relatives, the first large group of 127 went there in 1804. Milliken states that a total of 161 Tatcans were eventually baptized.

They would have controlled the southern and western reaches of Mount Diablo where annual autumn Indian gatherings took place. Evidence indicates that the main Tatcan villages were in Alamo, Danville and San Ramon.

Volvon

The Volvon held the peak of Mount Diablo, the vast Marsh Creek watershed to the east and probably Clayton. The Spanish called Mount Diablo “Cerro Alto de los Bolbones” (High Point of the Volvons {Bolbons}) beginning at least in 1811. They went to Missions San Jose and San Francisco from 1803-1808, with a total of 108 (Milliken). They were mentioned as leaders in the Bay Miwok resistance as well. After the missions were secularized, Volvon descendants may have returned to their homeland. The Indian workers on John Marsh’s ranch, Los Meganos, have been identified by some writers as Volvon and Julpun.

Conclusion

It is clear that debates over how to deal with the powerful Spanish invaders began as soon as the first expeditions traveled through Bay Miwok land. It is also clear that the “gentle and peaceful” Indians whom Father Juan Crespi described in his 1772 diary were transformed within a few decades; they refused to return to the missions and forced the Spanish military to send multiple expeditions into today’s Contra Costa to subdue them.

Disease and tribal disintegration finally defeated them. At the missions, few babies survived and diseases such as measles, syphilis, typhus and smallpox took their toll. Mexican ranchos were granted to Californios on Bay Miwok homelands beginning in the 1820s and, following a period of Indian raiding and resistance, the European presence prevailed. By 1850 the California Indian population was estimated at 100,000.

Bibliography

Callaghan, Catherine A., Bay Miwok Language, Paper presented before the Bay Miwok Symposium, September 20, 2003.

Fredrickson, David and Suzanne B. Stewart, Grace H. Ziesing, editors, Native American History Studies for the Los Vaqueros Project: A Synthesis, Los Vaqueros Project Final Report #2, Rohnert Park: Anthropological Studies Center, 1997, pp. 43, 49

Heizer Robert F., ed., Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 8, California (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution), 1978. The two chapters by Richard Levy on the Costanoan and Eastern Miwok are important, brief summaries. See also William F. Shipley, “Native Languages of California,” pp. 80-90.

Heizer, Robert F. and Albert B. Elsasser, The Natural World of the California Indians,Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1980, p. 203.

Milliken, Randall, A Time of Little Choice, The Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area 1769-1810, Menlo Park: Ballena Press, 1995, pp. 240-259.

——————–, Table A-2, from current research, 2003.

Rosenthal, Jeff and Randall Milliken, Stephen Mikesell, Naval Weapons Station Seal Beach, Detachment Concord, Integrated Cultural Resources Management Plan for the years 2000-2005, Vol. I, Sept. 2000, pp. 2-13.

From Bay Miwok Readings, 2003