Traditional Bay Miwok Environment

By Beverly Lane

Father Juan Crespi, March 31 and April 1, 1772.

Bay Miwok homelands in the 1700s included Mt. Diablo and the surrounding valleys and hills, an area now developed as modern cities. But the vegetation, waterways, paths and animal life before the European invasion were very different from what people know today.

Spanish and American writers described California’s native environment in diaries, letters and histories. Traditional Bay Miwok lands in central and eastern Contra Costa County covered several ecological zones, from the river and delta to the mountains. A lavish array of riparian trees and shrubs, including bigleaf maple, box elder, willows, bay laurel (pepperwood), cottonwood, sedge and black walnut trees, grew near the water. Oak and foothill woodlands included oaks (of several varieties), buckeye, and grey pines. Chaparral appeared on the sunny, south and west-facing slopes. Perennial, native bunchgrasses once dominated the meadowlands, leaving the landscape green for long periods of time. Bulbs such as brodiaea and soaproot and various seed plants (clarkia, red maids, buttercups, chia) covered the landscape.

According to botanist Glenn Keator

Hundreds of different kinds of annual, perennial, and bulb-bearing wildflowers occur between bunchgrasses, providing a magic carpet of ever-changing color from March through early June. (p. 13)

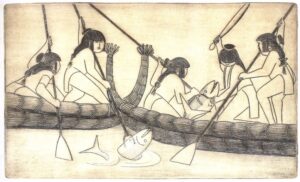

Eighteenth century waterways included adjacent marshes and wetlands which functioned differently from today’s controlled channels. Indians built their villages near the creeks so that they had a ready supply of fresh water and easy access to fish. Steelhead migrated up the Walnut Creek, San Ramon and Marsh Creeks until flood control barriers were built. The Tatcan lived next to the San Ramon Creek; Volvon lived along the Marsh Creek headwaters near Mt. Diablo and Julpun lived near Marsh Creek where it flowed toward the delta. Walnut Creek was navigable to Pacheco until the 1860s. Mt. Diablo Creek went across Concord, east to west, until Americans diverted it. This Creek had Chupcan villages along its shores.

Marshes bordered the Carquinez Strait and the delta and were full of animals, fish and birds. The Chupcan were a river people with many family relationships to the Suisun. The marshes are still in evidence, although much diminished in size. In Antioch a marsh once extended nearly to today’s Wilbur Ave. and this is true in many areas along the delta.

Drawing of Chupcan Indians fishing by Bunner McFarland

Animal, fish and birds provided a cornucopia of food as well as materials for clothing, whistles and dance regalia which the Bay Miwok created with precision and skill. There were herds of elk, antelope and deer, salmon in season and shellfish on the shore. Birds of every sort, from ducks to eagles, were described by one writer as “darkening the sky” when they migrated. Grizzly bears, mountain lions and coyote were often mentioned. Grizzlies traveled regularly across the San Ramon Valley from Mt. Diablo to Las Trampas, according to James Smith’s account.

Bay Miwok peoples managed the landscape by regular burning, pruning and digging. They set fires seasonally and purposefully. Fires ensured that seed harvests would be plentiful, killed disease organisms in plant material and kept woodlands open. After fires new sprouts proliferated, providing food for elk, antelope and deer. Such burns also produced long, straight, flexible shoots for baskets, straight and sturdy hardwood sprouts for digging sticks and straight poles for house building.

Basket weavers actively pruned and harvested plant materials such as sedge, bulrush and ferns. Grazing and browsing animals affected the grassland resources as well. Some brodiaeas, wild onions and other bulbs were important enough foods that some contemporary California Indians refer to them as “Indian potatoes.” Acorns, others seeds and bulbs served as important and nourishing food sources. As the women dug these bulbs, they would subdivide and leave immature bulbs for next year. To the Spanish and Americans the land may have looked untouched, but this was not the case.

Euro-American settlement brought innumerable environmental changes. The grasses which grow on today’s hills are exotic annuals (wild oats, Italian rye, foxtails, bromes and fescue) which came in soil ballast and on the coats of cattle and sheep brought to California with Spanish contact.

Many of the large creeks and streams have been channeled by County Flood Control Districts and the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers to protect modern residents from floods and facilitate building development in floodplains. In the 1800s silt from hydraulic mining in the Sierras altered the rivers, delta and bay. Development of agriculture, cities and highways have affected the animals, fish and birds which were here in the eighteenth century. Remnants of the native grasslands survive in small areas of the East Bay, but “few will ever be completely free of the (exotic) interlopers,” according to Glenn Keator.

Bay Miwok and their ancestors survived for thousands of years, managing the land in a way that was environmentally sustaining. Much of the natural world which they enjoyed has given way to twenty-first century developments. Their villages were located throughout their homeland, including the centers of Clayton, Walnut Creek, Oakley and Danville and many other locations now covered by commercial development, office parks and housing.

Robinson Jeffers’ poem “Hands” speaks to what could be learned from the change in the Bay Miwok homeland over the past 250 years:

Inside a cave in a narrow canyon near Tassajara

The vault of rock is painted with hands,

A multitude of hands in the twilight, a cloud of men’s palms, no more,

No other picture. There’s no one to say

Whether the brown shy quiet people who are dead intended

Religion or magic, or made their tracings

In the idleness of art; but over the division of years these careful

Signs-manual are now like a sealed message

Saying “Look: we also were human; we had hands, not paws.

All hail.

You people with the cleverer hands, our supplanters

In the beautiful country; enjoy her a season, her beauty, and come down

And be supplanted; for you also are human.

Bibliography

Amme, David, “An Introduction to California’s Native Grasses,” Manzanita (Berkeley: Regional Park Botanic Garden, Tilden Park), Vol. 1, No. 2, Fall 1997.

Blackburn, Thomas C., and Anderson, Kat, eds, Before the Wilderness, Environmental Management by Native Californians. (Menlo Park: Ballena Press), 1993.

The Fages-Crespi Expedition of 1772 (Pleasanton: Amador-Livermore Historical Society), 1972.

Heizer, Robert E. & Albert B. Elasasser, The Natural World of the California Indians (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press), 1980.

Keator, Glenn, Plants of the East Bay Parks (Niwot, Colo: Roberts Rinehart Publishers), 1994, pp. 13-15, 21-23.

Ortiz, Beverly R., “Following the Smoke II,” News from Native California (Berkeley: Heyday Books), Spring, 1999, p. 13 ff.

Roderick, Wayne, “Indian Uses of Native Plants,” by Pat McRae, Manzanita (Berkeley: Regional Park Botanic Garden, Tilden Park), Vol. 3, No. 4, Winter 1999.

Smith, James Dale, Recollections, Early Life in the San Ramon Valley, ed. by G. B. Drummond (Oakland: GRT Book Printing), 1995.

Wollenberg, Charles, Golden Gate Metropolis, Perspectives on Bay Area History (Berkeley: Institute of Governmental Studies, UCB) 1985.

From Bay Miwok Readings, 2003